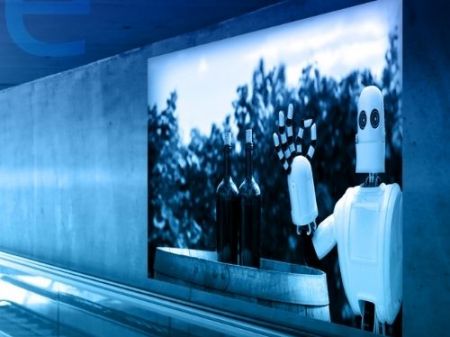

Sommeliers Choice Awards 2023 Winners

Behind the Romance of French Wine

Rod Phillips's new history of French wine shows the dramatic changes in how France makes, sells and consumes its national beverage

French wine is suffused with an aura of timelessness. An oenophile who makes a pilgrimage to Burgundy sees acres of vineyards that run right up to small towns with medieval churches and feels a powerful connection to a tradition that's hundreds of years old. A New Year's Eve reveler picks up some Veuve Cliquot, because Champagne is essential to any real celebration. A supermarket shopper buys a modest bottle of Bordeaux, because it has a cork rather than a screwtop and the label looks the way it would have a generation ago.

This sense of historical continuity may be integral to the commercial success of French wine, but it's also a myth, Rod Phillips argues in his new book French Wine: A History, a survey of the subject from antiquity to the present. Phillips, a professor at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada, fell in love with French wine when he was a teenager in New Zealand in the 1960s and remains a devotee, but he doesn't let his affinity cloud his historical judgement.

Start with the vines themselves. Until the late 19th century, they were scattered at random in vineyards. To plant a new vine, a farmer would either cut a piece of an old one and stick it in the ground or, in some cases, stick a piece of an existing vine in the ground, wait a few years and then separate the new plant when its roots were deep enough to survive on its own.

Phylloxera, the bug that devastated vineyards all over Europe in the late 19th century, led to a completely different way of growing wine grapes. Because the aphids destroyed the roots of vitis vinifera, the grape species from which virtually all wine is made, winemakers needed to develop rootstocks that could withstand the bugs' attack and then graft vitis vinifera onto the rootstocks, which came from other grape species.

That meant farmers had to select rootstocks and vitis vinifera varieties and clones to use - a choice they'd never had to make before, and one that became much more complicated with the rise of modern biology. Farmers also planted their vines in rows and trained the plants on wire, which allowed for the use of horses and, eventually, tractors.

Read more at source: TheStreet